Realizing that our time together was running out, I decided I might as well address the elephant in the room, satisfy my curiosity, and walk away from the relationship with some closure. So, I — comfortably sporting my hallmark mismatched shirt + shorts combo — turned to my first college roommate and blatantly asked, “My style disgusts you, doesn’t it?” Being the polite kid he was, he respectfully smiled, laughed, and tentatively nodded his head, “Yes.” It was nothing personal because, after all, I couldn’t care less about whether my socks matched my shoes or how long it had been since I last wore a given outfit; however, to him, a self-proclaimed fashionmonger, my entire wardrobe was practically a sin. The college experience often places you in scenarios similar to the one above, where you realize that, “normal,” is not quite as objective as you might have thought, and where you expand your understanding of both yourself and the rest of the world by exposing yourself to new spheres of thought and behavior. Of course, when your norms come into conflict with, “the other’s,” it must be them who’s the crazy or weird one, right?

In the late 1970s, Lee D. Ross, a psychologist at Stanford University, and his colleagues identified a stream of patterns and tendencies regarding biases that you can likely recognize in your everyday life today — such as fundamental attribution error and the hostile media effect. Of these tendencies, the false consensus effect in particular addresses the idea that we are biased to believe that our behavior is, “normal,” and opposing behavior is, “abnormal.” For example, since I grew up with a fanatic Rocky fan, former elite-level runner, and doctor for a father, waking up before sunrise to go for a run and drink a few raw eggs to the tune of Eye of the Tiger at age 8 seemed like normal behavior to me. And, as a consequence to being engulfed by this type of shenanigans and enthusiasm for exercise, playing sports, going to the gym, and eating a, “healthy,” diet have all become normal behavior to me as well. On the contrary, and despite growing up two rooms down from what would become a fashion designer, I didn’t catch onto the types of stylish habits that were ordinary for my previously mentioned roommate.

I imagine you can all relate to my circumstances, in that you probably have some thought processes, behaviors, and habits that have always seemed to come naturally to you and others that have always seemed to be awkward for or incompatible with you. For all of the beneficial mannerisms that you innately find attractive and all of the detrimental activities that you don’t, you’re in luck; however, what do you do with all of the deleterious habits and advantageous practices that appeal to and repel you respectively?

In last week's post, we discussed how to engineer your environment to favor your desired habits with concepts from James Clear’s Atomic Habits, and this week, we will continue this discussion with a new goal in mind: optimizing protocols to maximize the results you want and minimize time spent on activities you don’t like. In this regard, I find there are few people more helpful to look to than the productivity guru himself, Tim Ferris. I previously described some of Ferriss’ productivity principles in my post on The 4-Hour Work Week: Escape 9-5, Live Anywhere, and Join the New Rich, where he outlines his tips and tricks for ramping up your outputs in the business world and simultaneously winding down their costs. Here, we will explore some of the ideas from another one of his Best Sellers, The 4-Hour Body: An Uncommon Guide to Rapid Fat-loss, Incredible Sex, and Becoming Superman, where Ferriss walks the reader through his strategies for fine-tuning procedures in the weight room, kitchen, and more to amplify rewards and minimize costs through leveraging the minimum effective dose (M.E.D.), a concept built upon The Pareto Principle. The main premise is as follows: all interventions have some type of side-effect, as well as some type of plateau of returns; consequently, it is most efficient to engage in the minimum amount of an intervention required to reach a sufficient amount of rewards. In other words, if it only takes 2 doses of, “X,” pill to relinquish your pain, the pill exhibits some level of side effects, and adding a third pill only provides marginal improvements, then, according to the M.E.D. principles, you should only take 2 doses.

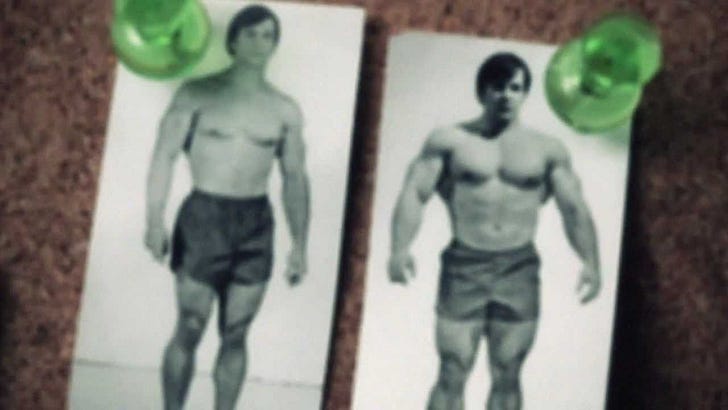

This approach is particularly valuable when it comes to the activities we don’t like doing but that we know will produce the results we want. For example, if you don’t like the gym but are looking to shave off some body fat and toss on some muscle mass, Ferriss outlines a lifting protocol that he claims will more than satisfy your goals for the low cost of two 30-minute gym sessions per week. Whether it be getting your beach body ready as the summer approaches, tweaking your sleep, or boosting your testosterone, this book offers countless simple and practical interventions, from cold-showers to slow-carb diets and more, that will help you efficiently achieve the physical performance you are chasing. For a preview of The 4-Hour Body and related content from the author himself, check out the links below.